Doubt to advocacy: The cardboard box experiment

In the complex world of device repair, every minute counts. Customers expect quick turnarounds, and businesses must balance speed with quality to remain competitive. But what happens when inefficiencies are baked into the very process meant to deliver results?

This is a story of a device repair facility grappling with a system that seemed too rigid to change—until a simple experiment with cardboard boxes transformed scepticism into belief and unlocked a path to efficiency.

The Challenge: A process stuck in overdrive

At a large device repair facility, orders were increasing dramatically —but the system was strained. Every device, regardless of the repair required, moved through all stages of the process. Whether a simple screen replacement or a complex internal repair was needed, devices went through the same sequence of steps including diagnostics, disassembly, repair, reassembly, and testing.

As the volumes ramped this started to show problems: overwhelmed stations, mounting delays, and frustrated customers. The team knew the system could be restructured, routing devices only to the steps they actually required. But confidence in the idea was low. Leadership worried that trying to change the process would only make the delays worse. “We can’t even keep up now,” one manager said. “What happens if we experiment and disrupt the entire workflow?”

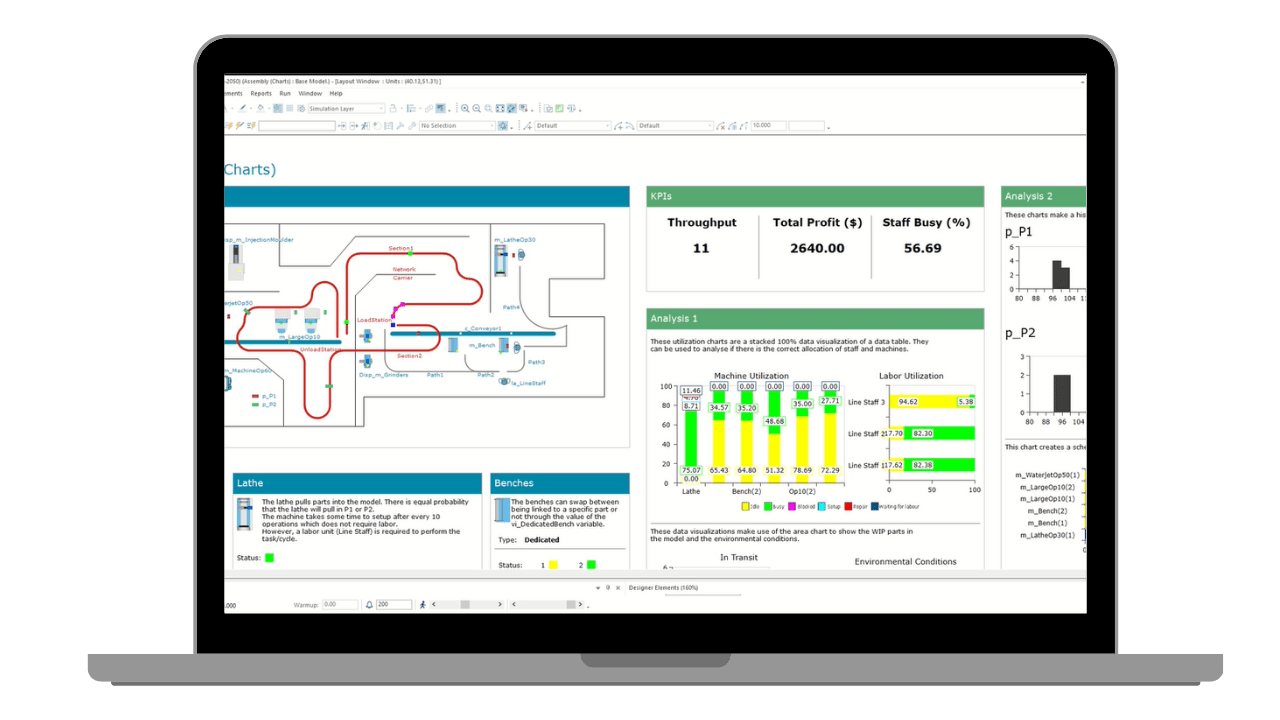

Seeking clarity, the operations team turned to a discrete event simulation (DES) model to analyse the flow. The simulation demonstrated a clear opportunity: by re-routing devices based on repair needs, they could eliminate bottlenecks and dramatically reduce overall repair times. Yet, despite the promising results, leadership was hesitant to act.

“It’s just numbers,” one leader remarked. “How do we know this would actually work in real life?”

The Experiment: Bringing simulation to life

Faced with scepticism and frustrated with the inertia, the team realised they needed to bring the simulation to life in a way that everyone could understand. They decided to go ‘old school’ to the earliest days of simulation and conduct a low-tech experiment using a mock-up of part of the overall repair process—built entirely out of cardboard.

If you’ve seen the movie about McDonalds process development – Exactly that!

Using cardboard boxes and labelled sections of a table, they recreated the facility’s repair workflow. Different boxes represented repair stations, while a mix of coloured cards symbolised devices with various repair needs. Team members played the roles of workers, physically moving the "devices" through the simulated process, following the new logic proposed in the DES model.

As the group worked through the mock-up, the results became immediately clear. Devices that didn’t require diagnostics or extensive testing were routed around those steps, avoiding unnecessary delays. Bottlenecks vanished. Repair times dropped dramatically.

What’s more, the team could see, touch, and feel the flow of work, making the benefits of the proposed changes tangible. It wasn’t just a theoretical improvement—it was something they could experience firsthand.

The Outcome: Confidence built, change unlocked

The cardboard box experiment proved to be a turning point. By physically experiencing the simulation’s logic, the stakeholders’ confidence grew. They no longer doubted the accuracy of the DES model and embraced the proposed process changes.

With newfound trust, the facility restructured its workflow. Devices were routed to only the necessary steps, reducing congestion and allowing the team to process more repairs in less time. The results matched the simulation’s predictions, validating both the model and the experiment.

In the months that followed, the team continued to use simulation to refine their processes, extending the model to include full process changes, staff levels and supply chain interactions. The power of the model was magnitudes higher than originally envisaged due to early creative problem solving with stakeholders.

Finding your "cardboard box"

The story of the repair facility highlights an essential truth about simulation: the best models are only as effective as the trust they inspire. The data might be flawless, the logic impeccable, but if stakeholders can’t connect into their reality, it’s an uphill battle to drive change.

When introducing DES to your organization, ask yourself: What’s the equivalent of the cardboard box for your stakeholders? What tangible or experimental element can help them see the model’s accuracy and believe in its value? Here are a few ideas to get started:

1. Bridge the abstract and the real

Create simple, hands-on representations of the simulation to make its insights accessible. Look for simple ways that can help stakeholders engage with the data in a meaningful way.

2. Tailor to stakeholder concerns

Understand what’s holding them back or what is the true measurement they are interested in: Are they worried about disrupting operations? Unsure of how the model was built? Want to know about throughout, but really risk of failure is top of mind? Find ways to address their specific fears directly.

3. Start small and scale up

Demonstrate the simulation’s value with a limited experiment, like a single process or department. Success on a small scale can build confidence for broader adoption. Quick wins breed confidence.4. Make it collaborative

Involve stakeholders early and often in building and testing the simulation. When they see their input reflected, they’ll feel greater ownership and trust in the results.From doubt to advocacy

The cardboard box experiment didn’t just validate a process change—it transformed the repair facility’s mindset. What began as scepticism toward a simulation ended with enthusiastic adoption, unlocking new levels of efficiency and customer satisfaction.The lesson? Trust isn’t about convincing people with numbers alone. It’s about connecting data to experience in ways that resonate. Whether through a mock-up, a pilot test, or another creative approach, finding your stakeholders’ “cardboard box” is the key to moving from doubt to advocacy—and unlocking the full potential of simulation for better business decisions.

So, what’s your cardboard box?